In this episode of The 2pt5 innovator podcast my guest is Soren Hermansen. We are talking about empowering (on many levels, and yes, also with electric energy) a community. About the balance of transforming from the bottom up and the top down. About the opportunities of climate change. About starting locally and spreading globally. Also we are talking about navigating the unknown. And about the beauty of wind turbines.

About Søren Hermansen

Søren Hermansen is the director of the Energi Akademiet (Energy Academy) in Samsø in the Baltic Sea which is known as Denmark’s 100% Renewable Energy Island. After empowering the local community to change the local energy systems to renewable first, the Samso Energy Academy is supporting communities all around the world in doing so. The Academy receives more than 2,000 visitors per year.

“I work with climate change issues every day because it makes sense to change our local community to be far more locally oriented and decentralized in its sustainable development efforts.“

Søren Hermansen

Listen to the episode

Listen, subscribe & rate at Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, Youtube & the show’s news. Rate & recommend the episode at Podchaser.

Connect with Søren & find out more

- Soren’s Twitter

- Energi Akademiet Website

- Energi Akademiet Facebook

- Energi Akademiet Twitter

- Energi Akademiet Instagram

- Energi Akademiet Building

Mentioned in the episode & additional

- Samso island

- Soren Hermansen, Time magazine hero of the environment 2008

- COP Kyoto

- Report “The Danish Experience with Integrating Variable Renewable Energy“

- Brundtland report

- COP 26 Scotland

- Not for Profit organization

- City of Wolfhagen Germany – Energiewende vor Ort

- Energiewende Öko-Institut, Wikipedia

- The 17 goals – UN Sustainable Development goals

- Evolutionary Leadership

- Open Space/Shared Space Meeting

- Greta Thunberg Twitter

- Bill Gates getting to zero

- Land Art The Lightning Field by Walter De Maria

- Climate Change heros

The Logo

And now what?

Check out the Energy Academy Pioneerguide and consider training in the academy to start transforming your community.

“Power without love is coarse and ruthless. Love without power is sentimental.”

Samso Energy Academy Pioneerguide

Newsletter

Transcript

This manual transcript was created by podcasttranscribe.com

Søren Hermansen: So my name is Søren Hermansen and I’m the Manager and Director/Leader -I don’t know, the title is not so interesting- but I’m on the island of Samsø, in the middle of Denmark. And I’m speaking from the Energy Academy, which is a kind of energy meeting house that is the center of many visitors and many actions on this little island to make it more sustainable and to kind of point into the future and build capacity to meet the challenges of climate change.

Klaus Reichert: Welcome, Søren, to The 2pt5 today. Thank you very much for taking the time for this conversation. And you said that you are on Samsø. And I’m sorry that I’m butchering all these names. I think Danish is very difficult to pronounce for people that are not Danish, so please excuse that. But Samsø is an island in Denmark, in the Baltic sea. What is around you? Please give us an idea of how the island looks like or what you see when you look outside of the window.

Søren: Samsø is mostly a farming community. It is… I see fields of grain, wheat and barley and some grass and if I turn around and look to the east I see the rising sun -it’s morning still- and then we have the sea and if I look further out, I see Zealand, which is the bigger island where you have Copenhagen. The Danish capital is positioned on Zealand. And further away is Sweden on the backside of Zealand. I can’t see Sweden but I can see it’s about 15km in direct line from Samsø to Zealand. If I look in the other direction to the West, I see Jutland and there’s a couple of islands between Samsø and Jutland. There’s a little bit longer, maybe 20 km to Jutland from the island of Samsø. And we see Endelave and Tunø, which is two little islands, And then you have the mainland Jutland, which is a peninsula that is connecting Denmark to Germany where we have the border near Flensburg and the south area of Denmark. So that’s… we’re right in the middle of Denmark, so to speak.

Klaus: You are on an island, it’s a small island and you have created something very special some years ago around energy on your island. And when you start reading about all these changes, all that transformation that you were working on, it looks like that Samsø is a model for sustainability, is that true?

Søren: Yes, the Samsø project started a long time ago. In 1997, we had a minister of the environment, Mr Sven Auken, the late minister of the environment. He passed away some years ago, but he was a really ambitious and very courageous minister, which I think ministers should be. [laughter] And he he went to Kyoto, in Japan, which was then the third COP meeting after Rio, in 1992, where the world decided to follow the Brundtland Report, where they talked about biodiversity and taking care of the environment, which then became the running COP meetings where I think we have COP 26 now in Scotland this year. So the third COP meeting was in Kyoto and he promised, my minister, that he would announce in Denmark, a community that could fulfill the Danish ambition to be 100% self-supplied with renewable energy. And to be running for this competition, we had to send in a master plan indicating how you, in 10 years, would make this… what do you call it… this transition to renewable energy. And Samsø won this competition. And then from 1998, I was the first staff, I was hired to kind of be the manager of the project, which was… I mean, nobody really knew where it would go, this project. A lot of very conservative old people said, “Yeah, that’s fine. It’s from the capital, it’s from the parliament and from a minister.” They talk a lot and they don’t know how, in practice, make this happen. So we had a lot of discussions about this on Samsø. Was this a good project for the island? Could we do it? Would it help some of the problems that we had here, namely an aging population, lack of good jobs and the young people moving away to go to the big cities, to go to university and be educated and stuff like that. So, I mean, you probably see that in Germany, and many other places also, that the rural area is suffering from what we call depopulation and aging population because urbanization is happening while we’re speaking here, everywhere, and the big structures are centralized more and more. So yes, it was kind of a chance that we won this competition and then started a new innovation which was the transition. Instead of having imported oil and fuels from outside, we started producing our own energy locally, which was also transforming the economical flow. So we could call it a modern version of an old first version of circular economy and the thinking of a good household economy, where instead of importing and exporting, we started using ourselves, which is a much better, much more healthy economy because it also produces jobs and innovation. And the money you gain from producing and selling energy to your neighbor will then be used to build a new house. So it starts… what do you call it… a much more balanced economical evolution on the island, which has been very good. And this is also why we are today a good showcase for local innovation and development.

Klaus: It started as a competition. But then you have to be willing to take part of that competition. You had to be a group of people that sort of came up with the plan and that supported the plan, also. It took time and possibly money to come up with all these plans. Did you have enough support in the beginning from the community in Samsø to do, to start such a transformation?

Søren: That’s a good question because, I mean, this is one of the key questions I’m showing you now, just for the audience, that I’m showing you the report. So this is actually the 10 year report we wrote for the minister. And in this report we actually indicate, year by year, how we were going to make this transition. And that’s the technical part, that’s kind of the engineering. And for the engineer, this is a recipe, this is a kind of a manual for transformation. But it doesn’t work when you go out and speak with people. They say “that’s fine, you can go to hell with your manual because I have other things to think about.” And this is kind of the, I think my biggest achievement in this, also. I’m not an engineer. I’m actually educated as a farmer and I have some other short term education as well as a communication person for environmental change. I, very quickly, the hard way, learned that it was not about technology, it was not about the tools, but it was a process of change that has to be kind of manifested in people’s heads. So we actually kind of made it a habit to ask the question before somebody gave us the answers, which is all in this report, that we have all the answers on how to do it. But the problem is that you don’t understand that if you haven’t formulated the question before you get the answers, so we had to kind of reinvent ourselves and start asking questions. What is the biggest problem on this island in 1997? It is lack of jobs. We had a big company that just closed down and 100 people got out of work and that was a big depression on the island. Of course you could speak to these people from two different dimensions. Either, well you can move away or you can find another way to live or let’s look into this new adventure and see if there’s any jobs in it. Maybe if we look at this job, it could be the answer to our questions, namely, how do we create a steady flow of good jobs that could create an income so people can make a life there, they can have kids in the school and they can have their cars mended in the garage and the shops, and everybody will be busy because of action, because of the happenings, and good good structured jobs here. And then people started moving and thinking, “oh, maybe we should have a look at this crazy project from Copenhagen, from the capital, from the minister and rethink our own… what do you call it… conservative picture, our image of this island being a farming island with primary production of pig, pork meat and bacon and potatoes and vegetables. Maybe we could also be energy farmers and produce our own energy. And so the first 1-2 years was a long process of a lot of talks and a lot of coffee and a lot of… what do you call it… motivation, and arguing, and stuff like that. And I think that was a very healthy process because we needed this discussion on the island. Who are we in 10-20 years time and what will happen to this little island and this community? And if we have, like, a status quo, we don’t do anything, what will then happen if we act and do things here? So what could happen potentially if we do something right now and then roll that back, kind of backcast it until today to get to this adventurous point of evolution in 20 years time. What do we do today, tomorrow, in three days, in three months, in three years? And then starting taking little steps in understanding our own role in these steps here also. I think that was a grand adventure for us 20 years ago because it kind of led to a lot of very healthy and very good discussions locally about the destiny of a small community.

Klaus: So it was a process. You were willing to do a process. You are willing to participate or support that process, to facilitate the process, also, and it was not something like a chicken or egg problem, where… You solved that problem in a way because people… there was a solution available, but a technical solution, but you also solved that social innovation side of the problem, let’s put it that way.

Søren: Yeah. That’s exactly right. The social relation had to be reconsidered also, because I think what is happening in the farming culture is that the farming culture was strong in 1920 and 30. There were a lot of hands working there before the industrialization of farming, where you have big tractors and a lot of machinery. There were a lot of person hands, man hours, in the production of food and that was a grand period of farming because the communities were thriving, there were a lot of people there and a lot of activity. When mechanisation and industrialisation happened, then the number of people needed for producing the same amount of food or even more was shrinking, which kind of left the farmers a little bit out in the fields alone and the community they were surrounded by before, which was kind of a food chain of many things because of the centralized… the central farm which produced all these actions here: the dairies, and the slaughterhouse, and the market and all the other things here disappeared and became supermarkets and export only. And that kind of left a depression. And the farmers are not so easy to kind of.. [laughter] to kick out, so they kept kind of a power structure in their mind, but they didn’t have it in a social relation. So socially they lost the power, but… what do you call it… influential or lobbying, they still kept the same image of them being very important. So I think they missed the evolution or the change of time and they missed realizing that they actually didn’t lead anymore. They were not the major… what do you call it… the influencer on how the society was formulated. So this energy project kind of gave… it was a neutral project. It didn’t belong to nobody. It was not like farmers giving up. They could still take part because they had the land, they could produce the straw for the biomass bio boilers. The heating system was then fit: instead of oil we used straw from the farms and the fields were now covered with windmills and solar panels, so the farmers regained their strength, so to speak. So they became ambassadors for change instead of being kind of resistant, the opposition and say, “we need to be in charge otherwise it doesn’t work.” So it was a nice opportunity to restructure society in a new way.

Klaus: And it left farmers or people that own land with their original purpose of doing something with that land, harvesting something from that land. It might be crops, it might be straw for renewable energy also, but it might also be wind energy that is provided to the grid and to the community. So there these people are getting the importance that they have in their mind, back to the community.

Søren: Yes, exactly. So I think we kind of restructure the… what do you call it… the hierarchy of things, which I think is necessary for society. It’s like biodiversity. You need to have big trees and small trees in the forest, otherwise it’s not a forest because the small trees are protecting the big trees from the wind that comes in here and so on and so forth. It is the connection of things that is important. It’s not trying to be individual or have the monopoly of things here. It’s a multiple… what do you call it… faceted thing of… and you can’t really describe how it works, but there’s a certain order that has to be there so people understand that now we feel safe. It looks like we have everything under control, if we can say that. [laughter] It’s not really under control but we understand the setting of things.

Klaus: What you had, you had a plan, you had some funding, you had some political backing and you knew how things were, technically. So you have to do some social innovation and social innovation happens a lot through communication and getting around with people. You said drinking a lot of coffee, which is famous in Denmark, but also it has a lot to do about education. So you need a place that helps others to understand the next steps. And I think this is where the academy comes into place. How did the academy get started? Was that part of the initial plan?

Søren: It was kind of… it was in the… we talked about having an energy house which was kind of an exhibition-meeting-education place where people could come and meet and stuff like that. And we wanted to have it near the public school, so the school kids could use it in the daytime and the adults or the citizens could use it in the night time. It never really happened because we couldn’t… I mean the school… that’s two different economies and two different systems, so it didn’t really work. So in the first 10 years we didn’t have the energy academy. We rented space in public buildings and in other places and we had these meetings. But we learned also. I mean it was not all funded. We have something called the feed-in-tariff, which you also have in Germany, for wind power and solar energy where you have a fixed tariff for the kilowatts you export to the grid, so net metering arrangement for solar panels and a feed-in-tariff for winter. But we also had that. So when we set up a budget for our winter buying of our solar park, we needed people to bring in their own money. So it was also a kind of a trust thing, where we built little companies, little cooperative ownership models for this also. And that was also an educational process for people to understand that I can be part of this with even small money, but I can invest one share, two shares, five shares in this project and be a member of this also. So it’s creating this cooperative feeling of being a member of something that would build up and kind of generate income and you’d have a little profit from it, also, you could use for other things. Yes, it was… it’s quite interesting, because a lot of people are not business people, they are just normal workers and they get a salary every month and that’s fine. But here they became kind of small time investors. [laughter] And we had to train the bank also and get a new relation with the bank so they would secure the bank loans so people could invest their money in new structures and also rebuild their houses, put in more insulation. So it became a food chain of action where we needed… every time we introduced something new, we needed to have a lot of meetings where we invited specialists from outside to teach people about the consequences of action. So capacity building was a very, very crucial factor of the innovation. If we… because information and knowledge is key to decisions and action. People don’t… they are afraid of doing things if they don’t know, if they go into the unknown. They become unsure and then it becomes an uncomfortable process. To make people more comfortable you need a bank to say, “this is a good idea.” And then people, “Ah, ooh, that was nice because I don’t like to speak to the bank about bank loans because they already say to me, ‘you have too many bank loans. You need to cut down your economy’.” [laughter] And so we needed to kind of pave the way, so to speak, and make it easy for people, not totally easy, but make it easier, so people could go into this new endeavor and try something they never tried before and and help them be comfortable and and not lose it or not making mistakes. Because we also knew that if we made too many mistakes in this and the people would say, “oh, this is dangerous. So let’s stay out of it.” So after 10 years, we then built the Energy Academy. We got enough money and funding to build this house here and since then we had a growing number of visitors from all over the world. And we still do municipal and town meetings also for people here. If there’s something we need to do to discuss, then it happens here at the Academy. Um, so people accept this as the meeting house for energy and, and sustainable development.

Klaus: Are you organized as a cooperative? As a genossenschaft in Germany?

Søren: Yes. Yes. Yes.

Klaus: A cooperative is a very smart way to sort of build ownership in a larger thing, which is originated, I think, from agricultural problems of having… of sharing, say, heavy machinery for farmers.

Søren: Yes. No, no. We use that model quite a lot because this is well known here, in the farming community, that is a respected and well known way to organize, so why not use it? Because people already have trust in this ownership structure. And then the other thing is, it is a not-for-profit structure. We don’t generate money here. So if we make any money, it’s in a party, we reinvest it in society immediately. So the owners are not taking out money for themselves for private use. It’s all designed in the ownership model that every income here is either used for hiring people to help us do things or to invest in new structures. Right now, we’re actually looking at the infrastructure for electric vehicles because we need more charging points, like charging stations, where we can plug in and and charge our vehicles here and which is not happening automatically because this is the free market that is supposed to do that and they don’t do it because we were so few people here. But we have a lot of visitors in the summertime, a lot of tourists, so we need to service them so they safely can bring their electric vehicle here and plug in. And we have a lot of German visitors here in the summertime and they bring their plug in vehicles and, of course, they need electricity. And if they couldn’t get it on an energy island where can they get it? [laughter]

Klaus: [laughter] And since it’s fresh electricity it’s even better, and your car drives much better that way!

Søren: [laughter] Yeah.

Klaus: I know we drive an electric car, a Volkswagen ID3, and it’s great, it’s just so different and it’s not different at all. Um but it’s a good feeling to know that a winter brand, a natural source, has produced the electricity to drive the car. So you created the Academy that was mainly focused in the beginning on communicating and teaching and aligning and bringing together local people to start that movement on the island, to start that transformation on the island. But that somehow has transformed also because now you are inviting, or for many years, you’re inviting people from outside the island from all over the world to teach about the results of what you were doing and about say, visioning of the future, of the future of energy, also. And how has that transformed the academy? How many people are coming, for example, each year? And I know right now with Covid everything is different. But what is what is going on on that level? You’re sort of reaching out now. What is your impact there? Who is coming?

Søren: I just saw a newspaper article from Denmark where somebody was complaining we’re not doing enough, internally, in Denmark for climate reduction or CO2 reduction. And then there was a list of countries where Denmark is operating, I think 20 countries around the world, where Denmark is involved in some kind of energy transition or support to erect wind turbines or to cut down on coal energy in Indonesia or a sector program with Japan or something like that. And I ran through that list and in 18 of those 20 countries we have been working. [laughter] So we are, you could say, we have been, I mean, I’m sorry to say that, but before Covid I was traveling sometimes 100 days a year, all over the world, which is my own private CO2 emission, it’s not so good, but I’m also part owner of wind turbines and forest and trees, so [laughter] I’m compensating a little bit for this also. But there’s a great need for these discussions. So the community model that Samsø has been, or is now, is greatly asked for around the world as a door opener. How do we make a new project in Indonesia? You have 250 million people living in Indonesia and it’s mainly coal. The economy is coal because they have coal in the underground. And it’s a poor country, it’s a developing country, and they have to use their coal to produce enough capital to run this big country with so many people. So they were devastated by an earthquake on the island of Lombok next to Bali. And Lombok was ruined quite a lot, badly, and the global aid programs, they started helping them. And Denmark’s contribution was to say we will give you some money but we will ask you to invest it in green infrastructure, which means that you will rebuild Lombok but in a more sustainable way and start using wind turbines and solar panels and systems that we have been successfully developing in the Western world and try to introduce that. But for this you need a process and learn how to use it and adapt this, like we had to train to do it in Denmark and let’s use the Samsø example. So we are partners in an international aid program that helps these people organize a new technological evolution which is more green and more sustainable than it was before. And these people will come back to Samsø on study tours and we’ll produce workshops here at the Academy where we’ll train the trainers in how to make the energy systems and send them back home so they can be their own teachers after this. So this is kind of the way we act as door openers and make these connections and networks and bring people back and train them and start having a global network of entrepreneurs who can work with sustainable development. And we do that generally all over the world. We… before Covid, we had like 3000/4000 visitors per year at the Academy, which is maybe not a lot as seen in a big perspective, but they are all kind of workshop participants. It is a big number to work with because we keep working with them after they leave the island. It’s kind of a constant developing network of practitioners, which I think is really beautiful.

Klaus: So you provide your expertise internationally, you use that to bring people also to your island so that they learn more about your processes, about your best practices, your next practices also. And… but who is coming? Is it like policymakers? Is it engineers? Is it creative people? Entrepreneurs? What is their focus?

Søren: It’s all kinds of people. It’s very interesting. It depends on what level of evolution you are on. Sometimes it’s presidents and kings and, I mean, ministers from different places. I mean, we have… we’ve had it all. And sometimes it’s a group of farmers from a farming community in Finland. Or it could be a group of citizens from the town of Volkswagen in Germany where you have energy… you have a sustainable energy development, where they want to see, they are doing very good themselves, but they want to kind of go out and be more inspired and, and do more here. Or it could be students from a university in Japan who have sustainability as their main master and then they go, they come here and stay for a while to learn about this. So it’s kind of, it’s all levels of community. I mean, we also had a group of housewives from America. Housewives for sustainable development. So I think we can’t really name them in one group, but it is organizations who are either in the starting position or in the middle of the development process where they realize that we need to know more, we need to learn more and be inspired to take the next step. And for this, I’m now showing you one of the projects here, which is called “Here – a Guide for Local Pioneer Communities”, which is kind of a guidebook, a handbook we use when we do these processes and it’s divided in many different cards where we use them as inspiration for the talks we have here. And this guide is formulated as 20 years of experience on Samsø condensed in sentences. [laughter]

Klaus: Nice!

Søren: [laughter] Yeah. And it’s really… it is a nice tool because this is… it’s called “Here” and I have it in my bag when I travel around the world. I’ve been working with First Nations in Canada for many years, also. I’m a mentor in a First Nation program, because they have a lot of off grid communities, and I bring this guide and it says “Here”, which is in the middle of Canada, “here”. So it’s always “here” because this is where it’s all about. I mean you have to have a starting point which is right here, we are in the right place, in the right position and the starting point is now, here, and I love this because this is making Samsø just an example, not a model, and we can inspire each other because it is all about here, where they live, the other guys. And I think that is maybe the most important for me to say that Samsø is not really a recipe for change, but it’s an inspiration for other people. And this is where you meet real people face to face and you can ask them questions about “how do you feel about this?” and you have this farmer, this plumber, or this politician saying, “well there’s a challenge to live here. There’s a lot of things we need to take care of” and have this realistic checking. It’s not just the fashionable showcase. It is a real life experience.

Klaus: I told you in the beginning that I really love Denmark and I think this is one of these examples why Denmark is so great and you really have to respect it, also. There’s so much going on in a different way of looking at things. So you have just mentioned one thing of how academia can be turned into action, into practice. Is there another thing, another like a next step that you advise to do if somebody came to you for example but wants to start something similar than you have done on Samsø as a community?

Søren: I think one of the things I have learned… I’m still learning in these processes, because things are also changing. Evolution is happening while we’re speaking. I have on my wall, also, the UN Development Goals. So you have like the 17 UN Development Goals and everybody is saying that this is really good and I agree, this is really good. But again it creates kind of a feeling of centralizing decision making. How can you have a global commitment to this, also? Because you need… in my head, you need to boil it down to the “here” [laughter] because you can’t say “yes, I agree”, and you have all these emblems where you have the the 17 Development Goals, and I sometimes, in a provoked situation, I say you should take them off and melt them, re-melt them and make shovels and spades and tools so you can start changing the world instead of just talking about it. And I know there’s a lot of political work to do to make commitments from states and make laws and regulatory… and make funding, also, for change here. So I don’t try to be ignorant or arrogant, but I just say for local people, it can sometimes be very abstract to hear about all the targets and the goals and things here also, where they miss the “here”, the feeling of what do I do? what can I do here also? And to start this discussion, I very often open with a “why?” not “how?” Because a lot of people want to have the “how” answered immediately: “How do we do this?” And then you have the answers and you can start doing it. I’d rather start with “why should we make change?” What’s your “why?” And because this brings in more social, psychological and human thinking in the equation instead of just technology and money and political decisions. It’s also like a social movement where you help each other being more brave and courageous so you can step into this new endeavor here instead of being, kind of, punished by threats of climate change: it’s going to be hell in a few years because we have rising temperatures and sea levels and stuff like that. “Ah Yeah, I know. So what can I do? I mean, let’s have another beer.” [Klaus laughs] I think it’s more like… it is… there’s things that we need to take care of. It’s kind of a household economy and this is making things more possible. That is my job. I like the possibilities. I don’t like to be an ignorant or a naive optimist but I like to be optimistic, anyway, because life is here and we need to live it. That’s our duty, to produce a good life and do it in respect with all the other life, which is also in connection with nature and what’s surrounding us, where centralized development has limits to how detailed they can go with this, also. So they forget about biodiversity. They talk about it but they forget about it because they are not biodiversity, while I feel more connected, living on a small island. I know my sea around us. I know how many fish there is in it. I know if there’s no fish in and I start wondering why, how come there’s no more fish? Maybe it’s because we have been over fishing or polluting the waters and stuff like that. Because I’m living in my society, where a lot of the politicians who speak about the UN Development Goals and other things, they live in a big city and they fly around in an airplane most of the time so they don’t live in the environment they are talking about. And I think this disconnect is one of the major problems of society. So I think the big job is to bring people back to having a relation with the nature they are talking about. And so they, instead of talking about nature, they become nature, if you understand. And I think that is sustainability in a nutshell, and seen from my perspective, this is where we can act and module and I think everybody has this little feeling of being part of something bigger, and they remember the time when they’re sitting around the campfire and are looking at the stars and having a really great time and getting… kind of… feeling that the world is bigger than you and you’re just a particle. [laughter] It’s crazy. And what can you do? I think that sometimes you need to get to that point.

Klaus: And also you need to have ways to envision the future. You said you need to create images, positive images and that’s something I do a lot in my work, also, because it helps others to see what could be there as a scenario, as a goal, as something… as a dream, even, which can then create actions and tasks. I understand that you do also work in that visioning sector. Is there a method that you like a lot? What do you do to help others create their positive image of the future?

Søren: Well, we have used different meeting forms during time because people are getting smarter and smarter also. I mean, we use something we call evolutionary leadership, which is that we don’t have a steady leadership, like hierarchical top-down leadership, in this structure. And we try to have a rolling or rotating leadership where we believe that leadership is about navigating in the unknown. And to do that, every year, one or two times, we have… -now Covid prevented us to have it last year but we hope we can do it again- we have a big open space meeting. So the open space meeting needs a lot of preparation because it’s not just the meeting, it is the meeting where you get everybody together in a big meeting and we have like very big circles of people. We can be up to 100-130 people in 2-3 circles, where we sit outside each other, and then we put the burning questions inside the middle of the circle and we start talking about what is the most important thing to focus on for the next 10 years. And we update that every now and again, and people are getting used to it, and they like this format because there’s no physical leader in it. We have a moderator, we have somebody who will lead us through the process, but the mayor is not the leader, and the director of the big company or the big farmer, they are not the leaders. We take their hats off and say, “You leave your position in the entrance and then you come in as a person, and of course we know you possess some capacity and some power here, also, so we don’t we don’t ignore that, but we don’t talk to you as the mayor but you can talk from your own position and what you see and what you think has to happen here.” And before we have the open space we have learned that a good… we call it a priming of the meeting. The priming is like when you paint the wall then you put primer on first and then the real paint afterwards, otherwise the real pain will not really cover. So priming is doing the ground… the basic work before you do the visual work. Primary is inviting like all the key players, all the leaders, both the obvious leaders and what you call the natural leaders. We have also people who are leaders by nature because they are… they have… they possess some capacities in leading processes and when they stand up and say something, people listen to them because they are respected for their insight and their intelligence and the way they can organize. And we call that shared space. So before an open space we have a shared space meeting, where we talk about what is happening in society, what are the challenges, what are the possibilities and what are the barriers for development? So we are well prepared for this because if we ignore this and have an open space meeting where people are just out of their mind, thinking about, “Oh, it could be nice to do this and this and this,” if it doesn’t have a basis then it becomes visions only, and visions only are dangerous because then people go home and then what? I mean, so Monday morning, it’s a normal work day [laughter] and reality kind of kicks in and puts you back in the same position as you had before. To create these little, what do you call it, nurseries of new thinking and new… you have to do it from the positions you have today and to have that, you have a trusting kind of examination of what that level is. So the shared space provides the question that we then talk about in the open space.

Klaus: Mm-hmm.

Søren: Because then you can be sure that somebody is actually… they are holding these questions as a newborn baby. I mean this is my responsibility, to carry this idea, and make it live, and nurse it and feed it so it grows and becomes something.

Klaus: I don’t want to get too technical. But the two problems or the two issues I always face here is how do you get people to understand that they have to take their hats off or wear another hat in that circle? And the other thing is what is a next step, after which appropriate time of visioning, to get into action?

Søren: I think sometimes leaders also like to have their hats taken off and not be responsible every time they stand up. They are kind of the leader here, especially in a small community where you meet the mayor in the supermarket or you meet the director in the football match, and stuff like that. You have different hats on in different locations already, so it may be easier for us. I mean if I meet the minister in Copenhagen on the street, it’s very unusual and even if I know this person, then it’s very difficult to have, like an informal conversation with this person because he’s surrounded by a secretary, and maybe security, and stuff like that. [laughter] Here it’s totally different. I mean, everybody is just, I mean, doing their shopping as it is more normal, so to speak. So taking people’s hats off is just an agreement we do here. And people like that, that they are not responsible all the time, 24 hours a day, but they can actually step out of their role and take part of the process here. And also because we have trained quite a lot, people can see that this has a lot of benefit, a lot of advantages to do this. The other thing is, also, when we then have… we finalized the days and we sum up on all the processes that happened during that day, people call meetings and say “I’d like to talk about this” and if nobody shows up then they can leave this meeting, go to another meeting. We have this open process structure where a good idea is maybe not a good idea, because it is only you who believe it’s a good idea. [laughter] So you need to respect that. Some ideas are not mature, they’re not ready yet and other ideas it’s more obvious that people will follow these ideas. And then you have like 3-4 good ideas that we then finally sum up and say, “how do we… what’s the progress of these ideas and how do we make them live and become stronger?” And then we make agreements and people write their phone numbers and email addresses on the statements so we can call them and restart the meetings with this commitment. We already signed up, we put our names and our telephone number, which is a commitment to make this happen. And I think this is where it becomes realistic that the commitments are our kind of proof of action, that this will happen.

Klaus: How important is partnering in this context? Nobody can do something really big all by himself or herself. Do you help to find partners to start something that has come out of such a process?

Søren: The Energy Academy tries to be neutral, so we are not a partner, but we operate very often as a project secretary. So in the construction or in the birth or the beginning of a process, there’s always a need for somebody who writes the minutes and sends out invitations and does all these sorts of things. And we know this is a crucial point of any new project’s life that we have the organization structure in hand. What we then can do is, when we start asking questions, is say, “Okay, we will find the expert who can help us in this process, another expert who can help us in this process. So we try to, kind of, instead of believing we can do everything ourselves, we bring in, we invite capacities from outside who can help us organize and get to the point where things start moving by themselves. And this… I mean, the acceptance of ignorance is important, that you actually make people understand that it’s okay to say, “I don’t understand”, [laughter] it’s okay to say “I don’t know how to do this.” But the idea is still good, so maybe we can bring in some expertise who can help us get over that point. So we start the process and we have a great network in Denmark and other places, also, that will come and help us.

Klaus: I like this idea and that’s something… a place that creates so many… so much impact on different levels a lot. What do you recommend to somebody that wants to start something similar in another country? Maybe around the globe, it doesn’t matter, just what would be some appropriate first ideas, visions or steps to take to do something similar that you do to create a similar impact?

Søren: When you have a community, a defined community, it could also be like a block of houses in the city where you said we need… I mean… we need parking places, where there’s more and more cars, where do we park our cars? So maybe we can start with that. And what if we then make free parking for electric vehicles? And what if… I mean, there’s many things you can do here, but start with the problem. If you have some problems, or kind of a necessary action, you can see obviously in front of you, we need to do something about this. And instead of having a wish for helping the world and be very idealistic, a lot of people are not idealistic at the same time. [laughter] So somebody had this great idea to save the planet and he calls a lot of people to say, “let’s save the planet”, and people say, “it’s okay, that’s fine, you can do that, but I’m busy. Maybe next Monday I can come back.” [laughter] But if you say, “we have a problem that… a practical problem. I mean, energy prices for heating have grown too much. Maybe we can make a collective heat pump system and organize this in a new way. Is anybody interested?” And all the house owners will say, “yeah, that’s interesting because I think it’s too expensive to heat the houses with gas from Russia”, stuff like that. So if you can point out some key, necessary points of action where people can relate immediately to this problem, and if you can solve this problem by some local collective cooperative action, then I think you have a case, then that’s a good idea as a starting point, then it can grow with other points also. But if you start with a high vision about very, very ambitious goals, then my experience is that a lot of people will be afraid of that. This is just a lot of “blah blah” and hot air and talks and somebody wants to promote him or herself as a politician or as an NGO and people will run away from that. Exception is the students’ Green movement and the university… I mean, you see some young people like the greater tundra effect is down so they don’t necessarily have a direct purpose beside asking the adults, the grown ups, the politicians to act now, [laughter] which I think is a very simple purpose but very important also. But… and you can say they don’t have their own house yet, and these guys, they don’t have, like a societal responsibility to feed a family. So I think the best they can do is to stand up and say, “somebody needs to grow up and do something here”, which I think is nice, but that’s different from a local community action. I just want to point that out. There’s nothing wrong with having high expectations about change, but a local project starts identifying some local problems that is obvious from many different points of view and people can see themselves in that. I think that is a really strong starting point if you want to do some action locally.

Klaus: I think it’s very, very important to be idealistic at the same time, but it might not be the only motivation to start something and it also depends on how… what your age is, as you said. I’m 50, I have different priorities and a different view on things and I need to care a lot more about other things than, or some practical things than just idealism, for example. And this is completely turned around for people that are 20, for example, but that is a driving force in society, that is progressing society also. Maybe it’s not always comfortable, but it’s helping to progress things in society.

Søren: So actually that’s also a point of interest for a local community. If we… In the beginning of this conversation we talked about de-population and aging population in many local communities, so we are actually somehow missing the revolutionary young guys who can stand up and say, “We want change and we won’t change now” because this is where they push the elder generation, like, I mean, I’m even older than you are, so I’m very comfortable in my own… what do you call it, organization, structure. I don’t have this urge for change now, but I sometimes need a kick in my behind as to kind of rethink yet that there’s a future for these guys, which is like 40, 50 years ahead of them, where we need to rethink how we, in a big circle, kind of reconstruct the world in a sustainable way with these guys on board, not just have it as, like, generational work here. The multiple faceted inside is really important. So I appreciate also that you recognize this. I think it’s really, really important.

Klaus: Well, it’s the 20-year-old in me that is saying that [laughter] because I’m kind of very driven in some ways and also limited in other ways. I have a background as an architect and I worked a lot with solar energy and renewable energy very early in the 90s and also did some regenerative energy research and consulting. So that was kind of my basic thing I’m operating from. So it’s not new to me to build wind turbines or use solar panels and reduce energy consumption. So it just took the society a long time to realize that there is importance in that issue. So I’m really glad that we’re having this conversation right now with an expert in the field of transforming energy, let’s put it that way. And what I was wondering is how important is energy to you? What is energy to you? What does it mean to you personally?

Søren: So, I mean, energy is a basic… what do you call it… resource for society to turn around. Energy is in my image… food, resources, in general, and fuel can be many things here also. So I think energy is… I mean, outside my windows right now we have sunshine and it’s producing, kind of, photosynthesis into the plants. This is also like an energy generator that makes the plants grow. So energy for me is a life straw that is making us tick. I mean, this is basically what it is. When we then transform this energy flow into, kind of, a market driven economical factor, then energy becomes money, it becomes a resource that can be… what do you call it… due to market mechanism, the market economy. And then we start… what do you call it… we start withdrawing from the bank, so to speak, because the flow of energy is all natural energy that flows into the system and we can use it without harming the balance of energy. Oil and gas is in the deposit, it’s in the bank. We put it in a bank [laughter] a long time ago and it’s actually supposed to be, to stay there. We can use a little every now and again. That’s fine. We have eruptions of volcanic activity. We have other things here also. We can use… I mean Icelandic people are very good at it. They just put a… it’s not… it’s actually very complicated. But they regenerate the volcanic activity, which is also a natural flow somehow. But when we start digging for coal and drilling for oil, then we add energy to the natural flow which is then bringing things out of balance. So for me, energy is the constant flow of natural energy, which is in all resources and all situations. And this is where, I think, we are compromised by a speculative market that is investing in fossil fuels and this is giving us inflation and problems to a degree we can’t control, which I think is really bad.

Klaus: So it’s common sense to produce wind, solar, regenerative energy and replace all these other sources that are non-renewable sources of energy.

Søren: Yes, that is the main purpose. Let’s keep it in the ground.

Klaus: How do you personally feel towards nuclear energy?

Søren: I don’t like nuclear energy but I can see some are arguing that if we want to get rid of CO2 emissions and stuff like that, then safe and modern nuclear energy is much better than any other other fuel energy, also. And I kind of agree with them. I mean, speaking from my own personal point of view, I think we should avoid it because it’s again a market thing and somebody is having the control over a centralized production and sending it out to a distributing system here, also, if you don’t have that as a state controlled unit, then you are in the hands of some… I mean, of the market. And the market is an unpredictable custom to be friends with. I mean it’s… [laughter] because it’s also speculation and somebody wants to make money out of it and I think the flow of energy should be kind of an accessible facility for everybody. It should be free, more or less. I mean, we can organize via the taxpaying but I don’t understand why energy is a market thing. But that’s because somebody has an interest in keeping it that way. And this is also one of the challenges in Denmark right now. We have more and more centralized energy systems, so the wind turbines are growing bigger, the solar panels are growing bigger and they are now invested in by the former fossil fuel guys. They have seen our green is good so they move their interests into green, to green energy, which, I mean, should be successful, we should say, “Yeah, that’s good! We want this!” and the market is now interesting for capital investors. But the problem is they only see the market thing of it, they don’t see the social impact of it, also. So they centralize things because it’s more efficient, and they take away what we built as a local innovator for creating jobs and growth locally. And we should be careful about that. And that’s also my argument against nuclear power. This is so centralized and so dangerous because it doesn’t produce anything locally, for nobody. But it could be, to be honest, it could be a solution for the emission of CO2, but it’s questionable.

Klaus: This is what Bill Gates claims famously…

Søren: I know, yeah.

Klaus: …that it’s basically the last 10% of energy that we can produce in other ways or that we can store in other ways. And I share very much of what you said. I just think people don’t think about the waste, the waste of nuclear energy, which is around for millions of years. It will be dangerous for hundreds and thousands of generations to come. And nobody, nobody, nobody has a solution for that. Nobody. Besides dumping it in the Baltic sea or something, right? So that’s not a solution. So it’s tricky. Energy is a tricky thing, in a way…

Søren: Absolutely. Yes, I agree.

Klaus: …because we expect it to be there but, in a way, it has to be provided in a very difficult way. I told you I was an architect a long time ago. My focus was more on concept and, and creativity and creating something together. So it was not really aesthetics. But let’s talk about beauty.

Søren: [laughs]

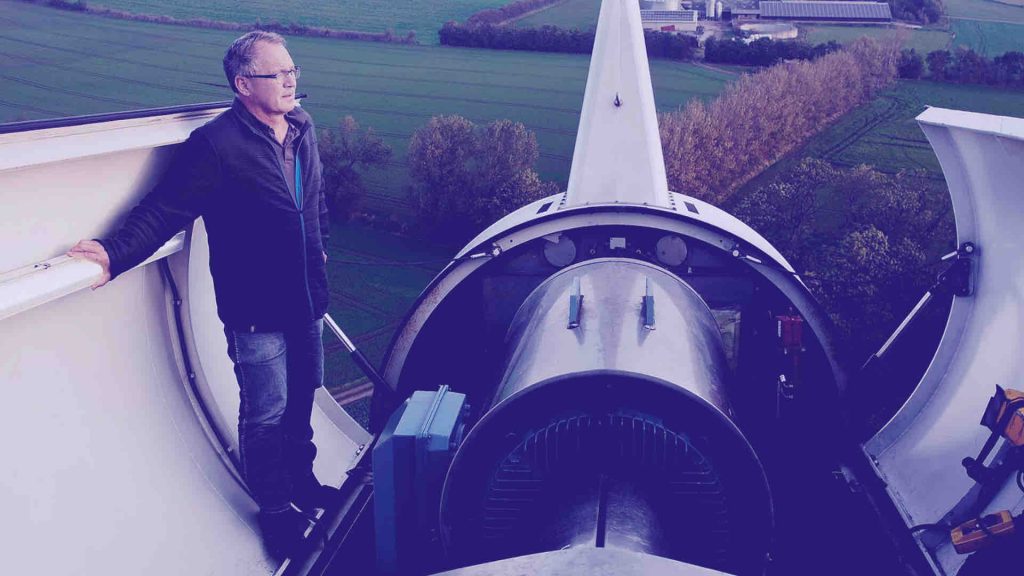

Klaus: I just saw a video about wind energy in Texas and they showed these two cowboy-type of people sitting on their horse, with stetsons and cowboy boots, and in front of wind turbines and surrounded by cattle and the older person said, “I really hated wind turbines. I thought they were ugly. Then I discovered I can make $10,000 per year for each wind turbine just for providing the land. Now, after installing 70 wind turbines, I think they are beautiful.” What do you think? The main argument against wind turbines is always, always, always, “I don’t like the looks of it.” It’s beauty, it’s something very, very individual that you actually can’t really discuss about. Especially not in a democracy where… well, the individual is important but the individual’s feelings is not always that important. But you have to handle all these things on a local community level. So do you like wind turbines? Do you think they are beautiful? I think there are. And how do you come up with a solution or an answer to these questions? Is it important to see the beauty in wind turbines or not?

Søren: I think the beauty comes with the practical reason for them to be there. I mean if you have… you can list up, what would make you more… what do you call it… more happy about being unable to have a wind turbine? Because I think it is… we have a lot of very abstract and very creative arguments against wind turbines. They kill a lot of birds and they do all kind of things. They make low frequency noise, so you can’t sleep and it makes you nervous, and stuff like that. And we have like three year studies of few people’s physics [laughter] and mental health and they can’t see anything. It is all… think… I mean, I don’t… I’m trying not to be ignorant, but I believe it’s about the disconnect of things. Where on Samsø we spend a lot of time talking about the next generation wind turbine, we had some old wind turbines and they were positioned in different places on Samsø, like little 55 kilowatt up to 250 kilowatt, very small wind turbines from the 80s. And we then said, we can take them down because they were very noisy and as they were speeding they ran very fast, so the rotation was stressful, also. They were not nice to look at in the same way. They had these letters towers, also. Now we have these tube towers and the rotation is really slow, very big wind turbines and we could replace many wind turbines with few wind turbines because they were bigger. And then we could also make a new position and put them where they made the most sense, not necessarily in front of people’s windows. And the last argument was to say, what if we then invite everybody who can see them to be part owners of the wind turbines? Like we have the cooperative ownership model as a… what do you call it… a principle for the erection of wind turbines. Everybody who can see them will be invited to be co-owners. And that helped a lot. I mean, if you’re a co-owner of the wind turbine, then it looks much better, it sounds better. It’s your wind turbine and it’s there because you were invited to be part of the process. It’s again about evolutionary leadership that you understand it’s not about my right as a farmer to put my wind turbine on my land. It’s my land. It’s been for generations. I can do whatever I want on my land. Yes, but you’re now putting a construction that is 100 meters high and it can be seen from every dorf and village around in your area. So you’re not a very nice neighbor if you claim this to be your right. Your right is also to be a nice person to your neighbors and behave like a citizen and a community person in this, also. And a lot of farmers here, they understand that, and we can talk about it because we meet the same farmer in the supermarket, in the football club, and other places, also. It’s not nice to be the stupid guy that is too selfish and egoistic in his partner. So I think it was not easy, but it made it easier for us to have this discussion before we erected the wind turbines. So we could have the planning according to some local values about ownership and participation and social inclusion in how to do it. I have seen some really bad examples also in Denmark, but maybe even more in Germany, the northern part of Germany. When you cross the border, then you drive into kind of a wind area that goes all the way across the northern part of Germany where you have a lot of wind turbines and I think you, being an architect, I think somebody should have looked at this landscape and said, “We need to place these wind turbines according to the landscape. So we don’t have this type here and this type next.” So it becomes one big, like, forest of wind turbines with many different models and scales and sizes. And this is making everybody kind of confused and say, “This is not nice, this is spoiling the landscape.” I think there’s some… a sign that has to be taken care of, also, that you put the wind turbines in a smart way, that you think about landscape planning at the same time. And I think you can solve a lot of problems. Then they can look nice. They can actually make the landscape more beautiful even. I mean, they can kind of stretch the landscape and make it higher and..

Klaus: Yeah, it can really add to the landscape. I always have to think of land artists, which used to be big in the 60s and 70s and there’s so many incredible pieces of art that came out of that movement. So, to me, wind turbines are oftentimes land art. But you were touching on a subject that is, I think, asking for the balance of top-down and bottom-up transformation because, yes, a community will provide the basis for the wind turbines, for example. But at least in Germany there’s a lot of planning, regional planning, and stuff like that, that is sort of a top-down thing that creates regulations of where to put wind turbines or build streets and stuff like that. So there needs to be a balance of these two things. Do you have an idea of how to do this best? I mean, you, Samsø, and your academy was created by a political instrument called a competition.

Søren: That’s a very crucial, very central question. I think what we need is a top-down framework, like a political decision. Like you had in Germany, also, like you had the Solar Evolution. You also have had a national wind policy where you have like a feed-in-tariff, a fixed market organization structure where you kind of lay out the frame where we, as local bottom-up actors, can move within. So the frame is given to us by the top down administration because your government, your country wants to be more sustainable or have a greener policy or more green energy. That’s a political decision. But how it’s going to be organized is then up to the bottom-up level where we can navigate within the frame, politically, that is given to us and the financial conditions for the project. I think that goes hand in hand and I think a smart government will do it this way and give autonomy to local communities, so it will grow from bottom up. Because then you avoid some of the resistance and “no” to nuclear, or “no” to wind, or “no” to solar. Because we’re not included. And I think you can get more inclusion if you understand the value of bottom-up and top-down working hand in hand.

Klaus: I’d like to shortly talk about your logo, and I will show all these things that we have discussed in the show notes. Also the logo, which is sort of something… a lot of sticks [Søren laughs] and individual lines forming a circle and a center, a focus point. What is… what was the reasoning behind that? I think this is… you already talked about it, but could you say it again please?

Søren: It’s a circle. At the same time it’s many different directions within the circle. So the circle is crucial to this also, but within this circle you have a lot of different… what do you call it… action points. Together, they formulate… So if you see it in the distance… I have an image on the wall over there somewhere. There’s kind of a t-shirt image, and if you see it in the distance, it’s also like a sun. It is this circular… what do you call it… image of action where everything has a center and then it spreads from the center. And I think this is again also the “here” and many other things, that we respect the individual action. We can’t control that. This is happening because of something. And then, if you then have a central energy, then it will happen from there. It’s a reaction. It’s not a nuclear reaction, but it’s a [laughter] reaction to some kind of energy that we can produce together. So I think that is what… I mean, that is a pre-discussion we had before we accepted the logo and we created this image of evolution.

Klaus: Søren, that was great, Thank you very much. This was so helpful and it’s good to see something being portrayed that will help other people to start something similar that you did to start a similar process. I do this because… I don’t know, it’s a hobby or I want to change things. I don’t know, it’s lots of time, but it’s really helpful what you did today, I think. Thank you very much again.

Søren: You’re welcome. It was a pleasure. Come visit someday. So we can have a coffee or a beer and talk.

Klaus: Thank you. Yes, I have talked to my wife about it. She said, “Samsø… that sounds nice. Let’s go there.” [laughter] And she liked, also, the energy aspect of it.

Søren: On the Pioneer Guide, you can see most of what is in here on the website. This exactly, we don’t usually send this around. We use this as a tool for workshops, so it’s not easy to read on your own. I mean, you can be inspired by it, it’s very nice, it’s a very nice design and layout.

Klaus: Mm-hm.

Søren: And the cards inside. It’s organized, you can say as this one “A strong, sustainable and robust community must share locality, activity and mentality.” And this is something… what we talked about. The mentality part is always the most difficult. How do you create a common mentality in the society? But on the flip side we have experiences from the island where we describe what happened in our community. Because we condensed this. We spent quite a lot of time interviewing people about their experiences. What did they learn that particular day? What were they thinking? and stuff like that. And another one is about leadership. This is my… I like this one a lot, “Power without love is coarse and ruthless. Love without power is sentimental.” And you can say that this is a local community. We need to bring power and love together. So the inspirational NGOs and hippies, they can cheat the business guys that there’s something else that money [laughter] and inspiration will be produced here, also. And again, on the flip side, then we have all the findings, here. How did we organize an ownership model where the business guys would give way for other people to participate? So we had a common and genuine feeling of ownership, so we could create a mentality of belonging and create a feeling of ownership without being real owners, but have a mental ownership and say, “This is a nice project. I like it, but I also accept that we need the business guys on board because we can’t carry this development only with visions. We also need some practitioners who can actually make it happen.” And these talks are brilliant.

“My vision of a Samsø that is self-sufficient in renewable energy – and in 2030 will be independent of fossil fuel – has required and continues to require constant effort. Not only my own, but a wide range of people. Together, we are taking responsibility for our collective, better future.”

Søren Hermansen